This column by Armine Yalnizyan was originally published by the Toronto Star on Thursday, December 22, 2022. Armine is a Contributing Columnist to Toronto Star Business featured bi-weekly.

Fifth in a five-part series on our year of extreme inflation.

There are times in life when wages or prices change the trajectory of your future.

You can’t afford to move out of poorly maintained or overcrowded rental housing. Or your wages don’t cover extra help for a child at the stage of development when they most need it. Or you’re so deep in student debt you grab the first not-great job that comes your way. Or find yourself saving less and less for retirement.

Tough choices can trim your aspirations. They can change the possibilities for those who depend on you. They can reshape who you think you are, and what you can become.

Rising inflation, falling purchasing power and fewer good job opportunities multiply tough choices, as well as the number of people facing them. Market dynamics and public policies shape prices, wages and jobs. Economics can create or destroy our control over how our own lives unfold.

That’s exactly why it’s so important that economists get things right, right now, with a possible recession on the horizon.

Economists have an evocative word for what happens when people lose out on life chances because of recessionary conditions; we call it scarring, and it happens when people enter a job market or lose a job in tough economic times.

In December, Tiff Macklem mentioned how worried the Bank of Canada was that the pandemic’s broad-based and protracted shutdown of the economy might “result in scarring … We worried that damage to the incomes and careers of a whole segment of the population, particularly women, youth and immigrants, would be permanent.”

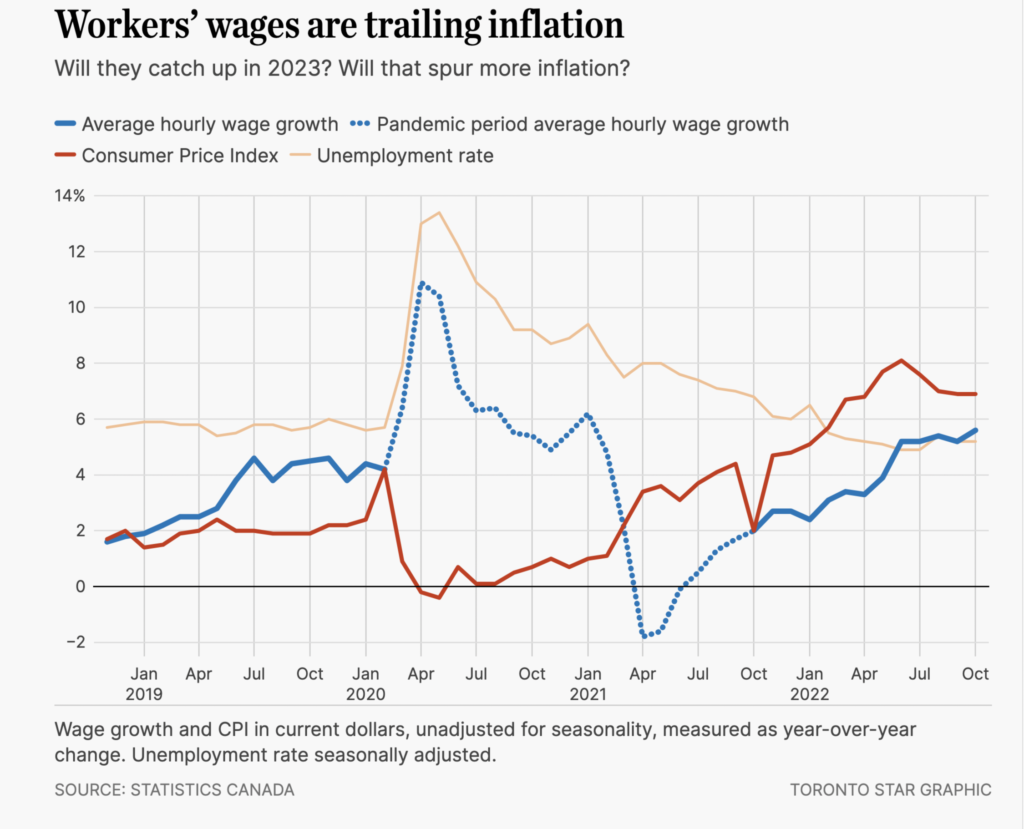

You don’t need to lose a job to lose a life chance. Right now the worry for many workers is that wages are not keeping up with inflation. Strategies to avoid losing ground can be seriously costly.

Some people will work longer hours to make ends meet, missing out on family and personal needs. Some will lose their housing, or their hope of escaping the rental market. Some will choose between food and meds, or heating and eating.

Ironically, the other worry is that wages will keep up with inflation, baking in a never-ending spiral of wages trying to catch up with prices trying to cover higher costs. Nobody wants that. Entrenched inflation is a recipe for longer-term misery.

While the history of wage growth is a mixed bag, and its relationship with inflation even more complex, we can untangle whether wages more often kept up, or not, with inflation.

In the 1950s and 1960s, earnings often grew at twice the pace of inflation. Low rates of unemployment kept pressures for higher pay up. So did the pressures of rebuilding the economy after the Second World War. Just as today, there were supply shortages in, well, everything: cement, lumber, roads, bridges, hospitals, schools, telecommunications, food and workers. Higher wages weren’t characterized as problematic. Inflation, schminflation, we couldn’t expand fast enough.

In the early 1970s, the pace of earnings growth, still high, started to moderate. After the first oil price shock in 1974, though, an economy dominated by manufacturing and construction — both highly unionized industries — saw earnings soar. So did gas prices and just about everything else we bought. Unemployment started climbing, but earnings growth outpaced inflation in the middle of the 1970s then kept pace with elevated inflation until the end of the decade. Which was the chicken, which the egg? It was far from obvious. But everyone was getting cranky. Rising prices, floundering profits and slowing opportunities. Time for a shift.

Enter the 1980s, and an abrupt downgrading of labour’s bargaining power. Unemployment soared not once, but twice. Hourly earnings barely grew for two decades. Two major recessions, the de-industrialization of the economy, and the ascendance of China and other low-wage zones’ factories saw the haemorrhaging of jobs in goods-producing sectors, and the mushrooming of jobs in the service sector. Many new jobs were lower paying than the jobs lost, and with more irregular or part-time hours. Meantime, some workers experienced huge pay gains. Poverty and inequality ballooned in equal measure.

The good news for workers of the era: inflation fell to much lower levels by 1991, and stayed there. Free-er trade promised to make everything cheaper; even you.

Then everything changed again. Canada rode a global commodity supercycle after 1997 as China expanded, with a never-ending thirst for oil and coal, iron, nickel and foodstuffs. Massive growth and profits for the export producers of the Canadian economy didn’t translate to solid wage gains throughout the job market.

The first two decades of the 21st century saw mostly modest wage gains tracking mostly low rates of inflation, but every time unemployment fell, a hint of the future already lay in these stats. By 2006, the unemployment rate had fallen to 6.3 per cent, then continued falling through most of 2008, rates not seen since 1972. From 2017 to 2019, unemployment fell from just above six per cent to below. In both brief instances, wage growth started rising, only to be halted by a global economic disruption.

Since June 2022, wage growth has been higher than it has been in decades, though still at less than half the pace of growth seen from 1974 to 1982. Average pay is improving at roughly the pace of the mid 1950s or 1960s. But back then, pay growth significantly outstripped price growth. Now, it’s significantly lagging inflation.

More wage growth is on the menu, as unemployment rates stay low and job vacancies high due to a wave of retirements by the baby boomers. Is that good or bad news?

The evidence provides three take-aways:

- Workers’ wages can be higher than inflation for a long period without being the primary driver of inflation (witness the 1950s and 1960s)

- Low unemployment has historically tracked more closely to rapid wage growth than the attempt to “catch up” to inflation. We are at half-century lows in unemployment. Any other factor of production is subject to the laws of supply and demand: When something needed is in short supply, prices go up. Why not wages?

- Reference to the dreaded wage-price spiral is usually a nod and a wink in the direction of the 1970s. It’s true wage growth eclipsed inflation in 1974-75 and 1979-1981, coincident with the inflationary hits of the oil-price shocks. But did they cause inflation? Despite other factors, that was the contention: labour is the problem, asking for more is making things worse.

That was the narrative then, and it’s fast becoming the narrative now. Business, banks and some governments warn asking for more wages is a bad, inflationary thing.

But workers are not asking for too much by attempting to ensure they don’t lose economic ground. And it will become increasingly politically difficult to suggest that is the case.

The smallest working-age cohort in half a century is tasked with supporting — through their wages and taxes — a large, growing share of the population that is too old, too young and too sick to work.

This isn’t a story for just a few years, as was the case half a century ago, when the economy was expanding at twice or three times the current rate. No. These pressures will be with us for decades.

History falls on the side of people’s lives being improved, not by being given more, but by demanding more. Demographics hand us a remarkable opportunity on a silver platter. Why not improve workers’ lives?

Ironically, resisted as it always is by decision-makers, that is what has always grown the system from which the powerful reap the most benefit. It’s a win for everyone.

Wages, prices and unemployment are at the heart of how we navigate our futures. The next chapter of this story of inflation and wage growth could be the gift we give each other in 2023. However it unfolds, it is ours to write.