This article was authored by Armine Yalnizyan and originally published by openDemocracy on Friday February 26, 2021.

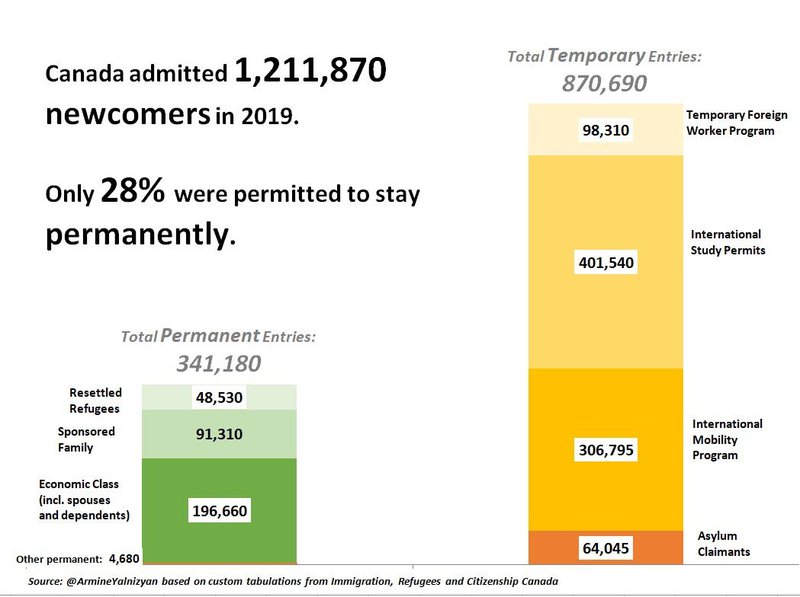

Worried about immigration during the pandemic? You may be shocked to learn that for every new permanent resident admitted to Canada in 2019, almost three temporary residents were admitted to work or study. ‘Immigration’ refers only to permanent residents, so any conversation about immigration is only talking about 28% of all the people entering Canada.

This little known statistic directly informs a recent conversation about Canada’s Immigration Plan at Ryerson University, the core theme of which is that we could miss a remarkable opportunity if we don’t see the whole chessboard. In particular, the surest path to an equitable post-COVID-19 recovery involves increasing the number of immigrants Canada accepts by expanding the paths to permanent residency for people already studying and working here, Canada’s temporary residents. That single reform could bolster Canada’s future in both the short and long run. Here’s why.

It comes as no surprise that Canada’s immigration intake was almost cut in half as a result of COVID-19, bringing us back to levels last seen in the late 1990s. Those levels are not good enough for the post-pandemic future, which will be marked by population aging and a shrinking working-age cohort. The pandemic accelerated a process already in play, with more people over 55 exiting the workforce than entrants aged 25 and younger. This dynamic hastens that moment when Canada’s net labour force growth goes negative if not for the addition of workers born outside Canada. A shrinking Canadian labour force, with little or no productivity growth since 2015, is a recipe for economic decline. That’s not a future anyone wants.

Nonetheless, some experts are worried about immigration minister Marco Mendicino’s pledge to make up for the shortfall in the 2020 target of 341,000 new immigrants by increasing targets over the next three years: 401,000 new immigrants in 2021, rising to 421,000 by 2023. For critics, it’s too soon for such ambitious plans.

COVID-19-related job losses and foregone hours of paid work means the current labour under-utilization rate, in other words, the unemployed looking for work, those wanting a job but have given up looking, and people working less than half their usual hours is more than 18%. Given that the pandemic hit low-income workers the hardest, and that low-income workers are disproportionately women, youth, racialized minorities and recent immigrants, it could seem counter-productive to add more people to the mix as the nation’s hardest-hit citizens struggle to find their feet again in the post-pandemic world. Indeed, the Conservative immigration critic, Raquel Dancho, describes the goal of accepting 1.2 million new immigrants by 2023 as “pure fantasy”.

Higher targets do raise legitimate concerns about the well-known challenges of integration, given the current inadequacy of settlement services. But is the Liberals’ plan really so unattainable and undesirable?

Consider the numbers: Canada accepted more than 1.2 million newcomers in just one year, 2019, through permits for both permanent and temporary residency – a number that had increased steadily over the years, particularly among those brought into Canada for economic reasons.

In 2019, about 30% of those who entered Canada as permanent residents had made the transition from temporary resident status. Point is, we can easily accommodate 1.2 million new immigrants over the next three years if we draw from the ranks of temporary residents who already work or study here. They have adjusted to life in Canada to some degree. Providing them with better settlement services like subsidized housing, English/French language, and learning supports, is a low-cost, high-yield return on public spending that also creates new jobs for Canadians.

Ironically, admitting more immigrants (i.e. permanent residents) may be the surest path to a more equitable recovery, given the recent policy evolution towards increasing reliance on temporary newcomers. You can’t build a thriving economy or a society on the permanently temporary.

We don’t know for sure how many want to stay, but there’s plenty of demand for pathways to permanence among the more than 530,000 international students, 459,000 migrant workers and 77,000 temporary foreign workers who were in Canada as of 31 December 2020, in the middle of a pandemic.

It is hard to believe that this deep well of human aspiration could not satisfy most, if not all, of the minister’s goal of adding an additional 50,000 immigrants this year. More generally, failing to integrate those who are already here studying and working and who want to stay is like leaving money on the table.

Though hard to imagine right now, we will soon be looking at widespread labour shortages. While population aging creates an unprecedented opportunity to increase skills and employment opportunities for whole groups of systemically under-employed Canadian residents, like the ones hardest hit by the pandemic, we’ll nonetheless need more newcomers to address temporary and permanent labour and skills shortages.

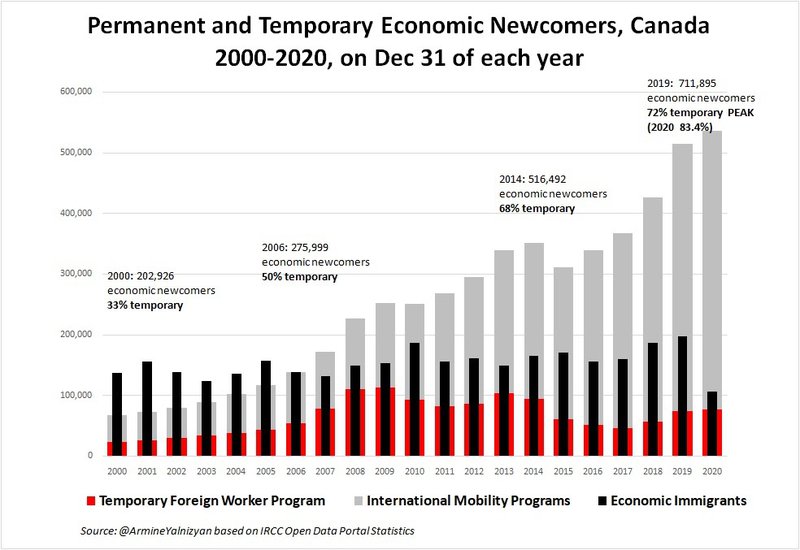

Historically, we have admitted more permanent residents than temporary ones to address labour shortages. But in 2006 the lines crossed. Ever since, we’ve admitted more temporary migrant workers than permanent economic immigrants. Take a hard look at the trajectory in Chart 2 and ask yourself: can you imagine living in a society where the vast majority of newcomers are only here to work, but not create community? Is this the future you envision for Canada, where labour shortages are met, but our economy and society are hobbled?

The shift described in Chart 2 erodes workers’ rights in industries like accommodation, food service, personal services, eldercare and childcare, long-term care, and some types of manufacturing. These sectors, which have long relied on low-wage immigrants, reduce costs even further by turning to migrant workers with even less ability to exercise statutory labour protections.

Exhibit A: seasonal agricultural workers, the essential workers who make sure we are fed, but may not be able to protect their own health and safety. Most come back, year after year; but this year some couldn’t even get tests or take time off when they fell ill with COVID-19. We can do better, for them and for us.

This process has begun. Small steps to create more pathways to permanence started in 2019, with a new pilot for personal care workers, joined by two others in 2020 for seasonal agricultural workers and live-in caregivers, and one for health-care workers in 2021. To these measures was added the recent federal invitation to basically everyone in Canada to put in an application to become a permanent resident.

In mid-February 2021 the federal government drew 27,332 people from these applications. Canadian immigration is based on a point system, and the lowest score of applicants was 75. A normal draw features applicants with 400 points, sometimes more. Does this downgrade the “quality” of immigrants and hence their ability to integrate? No. They were already here, studying and working, but at risk of losing their status during the pandemic, and deported. This was effectively a pro-active regularization program, legalizing resident status before it is lost.

In fact, Canada hasn’t had a major regularization program for residents without status since the 1970s, under Trudeau père. If not during a pandemic, when should such measures be taken? Never?

We should celebrate, not be afraid of these measures. Permitting more migrant workers to transition to permanent status increases their ability to access labour protections and basic human rights. If we reduce exploitation of these workers, we improve working conditions for everyone in the workplaces where they are employed.

The de facto ‘two-step immigration process’ that has emerged in recent years has been primarily driven by business demands for faster intake of newcomers, but could lead to better integration and lives for “low” and “high” skilled workers alike.

If temporary foreign workers are good enough to work for us, they are good enough to live among us, permanently, if that is what they wish.

Let’s not look at the immigration story with our eyes wide shut. How we live with others will define the labour market, society, and future of Canada.