This column by Armine Yalnizyan was originally published by the Toronto Star on Thursday November 25, 2022. Armine is a Contributing Columnist to Toronto Star Business featured bi-weekly.

Second in a five-part series on our year of extreme inflation.

Inflation is never our friend. That’s why we all want something done about it. But what is the “something?”

So far the main “something” has been the Bank of Canada — central banks everywhere, in fact — raising interest rates.

The plan is, if they raise costs and we buy less, demand will slow and give supply a chance to catch up.

After the most aggressive rate hikes in 30 years, is the plan working?

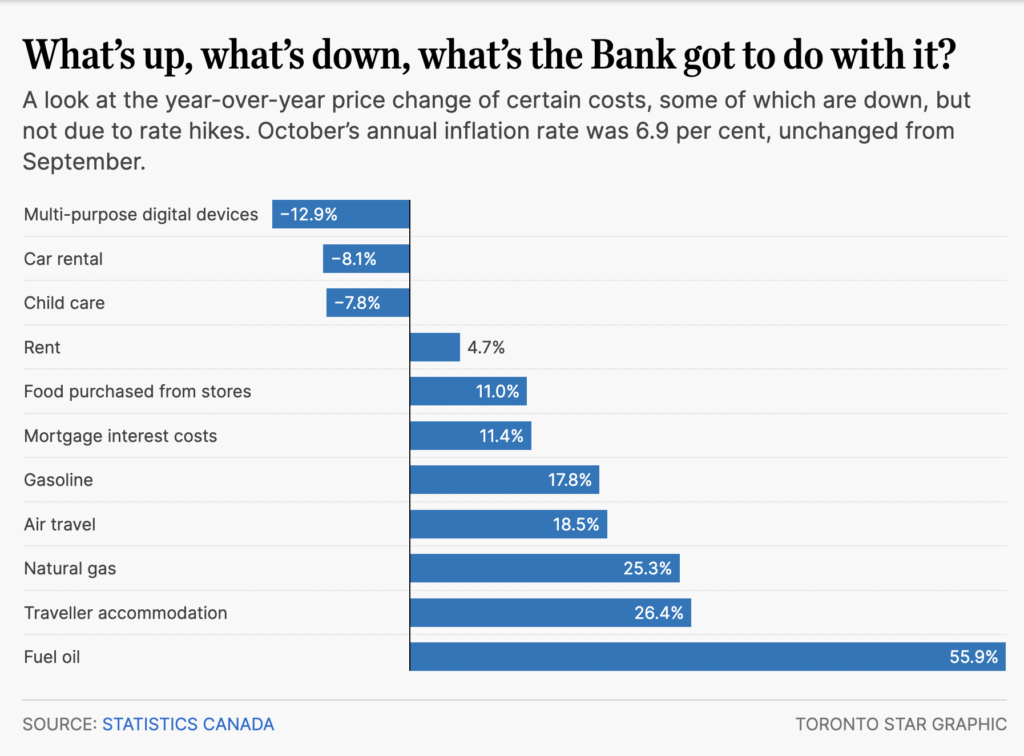

You may have noticed, even amidst the sea of maddening price hikes, some prices have fallen. Let’s look at the three biggest year-over-year price drops so far:

Digital media and multi-purpose digital devices (such as smartphones), down 15 and 13 per cent from last year, respectively. These prices have been more likely to fall than rise throughout the pandemic.

In fact, price cuts stemming from the application of digital technology are a longer-term story, affecting music, journalism and any kind of on-demand online service.

That’s because the marginal cost of adding another user is close to zero for digital products and subscriptions, whereas normally more inputs are required to produce more outputs. Digital technologies historically have had a deflationary effect, lowering prices for a wide range of goods and services.

Car rentals, down 8.1 per cent from last year. That’s only slightly down from the “carpocalypse” of 2021, when rental prices spiked 60 per cent. That’s because, in the first year of pandemic, fleets shrank due to high costs of maintenance and no demand during lockdowns; but when demand inevitably returned — surging far beyond previous years — there was a shortage of semiconductors for car production due to supply chain holdups.

Though the supply shortfalls are still there for an unusual range of factors, fleets have slowly been building back up. More supply, lower costs.

Child-care services, down 7.8 per cent from last year. According to Statistics Canada, declines in price started in April 2022. This is partly if not primarily due to an infusion of federal cash to lower costs of licensed care for parents in co-ordination with provinces and territories.

While another reduction is due in some provinces by Jan. 1, 2023, lowered fees for licensed care down to the promised $10-a-day level aren’t required everywhere until 2026.

You will note none of these price drops resulted from Bank of Canada interest rate hikes.

The price cuts that definitely are caused by Bank of Canada rate hikes are housing prices.

The average price tag for a house in Canada has fallen by 9.9 per cent since last year to just under $650,000 in October 2022. In Toronto, prices have fallen by 5.7 per cent, to just over a million dollars.

That’s great news for anyone with a suitcase full of cash, an unknown share of the roughly 35,000 home sales in Canada in October, of which about 5,000 took place in Toronto.

Most people have to borrow to buy a house.

For the 35 per cent of Canadian households with mortgages, carrying costs are 11.4 per cent higher than this time last year.

First hit are the 10 per cent of Canadian households with variable mortgages; but soon costs will rise for everyone who pays monthly for their shelter. That includes rent, paid by 37 per cent of households, or five million households.

Compared to last year, Statistics Canada says rents are up 4.7 per cent, though that number may be about to spike. As more people realize they can’t afford to buy a house, and more homeowners decide they can’t keep pace with rising mortgage costs, more people with higher incomes and bigger savings will squeeze into a rental housing market that is already undersupplied.

Some are already plunking down a year’s worth of rent to outbid other contenders. Those folks will push out those with lower incomes and fewer savings in a market that — between 2016 and 2021 — already lost 130,000 Toronto rental units costing less than $1,500 a month. No question, more have been lost this year.

Meanwhile institutional investors with deep pockets are eyeing the falling price of housing. Blackstone, a global investment business, is ready to spend $50 billion on real estate investments that all but guarantee rock-steady monthly returns.

They know: the future is about renting. We all have to live somewhere. Hiking interest rates isn’t lowering the cost of this essential monthly budget item.

Monetary policy strategy also hasn’t lowered food prices, which have outstripped general inflation for the past 11 months.

Last week I unpacked how volatile food prices are, because of ups and downs in crop yields.

Droughts, floods, fires and hurricanes have throttled supplies further this year, piling onto the impacts of pandemic and widespread labour shortages. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine also reduced global supplies of fuel and commodities such as wheat and oil seeds that become basic foodstuffs like flour and cooking oil.

Sure, there’s some wiggle room in what we eat and what we pay.

To a point, we can substitute cheaper foods and expose price-setting by providers with bigger market share, but the dominant reason we’re paying more is because there’s not enough supply, not too much demand.

Higher interest rates will dampen the borrowing power of small farmers and food processors, even agribusinesses, but their costs — and our prices — are swamped by an overarching problem: Simply. Not. Enough. Stuff.

If food prices do fall back down to Earth, it won’t be because of monetary policy. Cooling demand to let supply catch up doesn’t really apply to food. Even if we eat less, that won’t expand crop yields, bring a close to the never-ending Russian war in Ukraine, or stop climate chaos.

Then there’s fuel. Yes, the price at the pump is down from the eye-watering highs of the summer, but at last count fuel oils are up 56 per cent from last year, natural gas is up 25 per cent, and gasoline is up 18 per cent. Interest rate hikes have nothing to do with the volatility of those prices.

Right now the two fastest price spikes in Canada, beyond fuel and certain food costs, are travel accommodation (up 26 per cent compared to this time last year) and air travel (up 18.5 per cent). These prices have yet to respond to the strategy of cooling demand.

The 20th-century formula for controlling inflation when economies run hot can take between a year and a half to two years, according to the Bank of Canada, as well as bringing painful increases in unemployment.

In the 21st century that approach is more of a gamble because the modern-day problem is not enough supply, not too much demand.

Given underlying reasons for supply shortages, including demographic drivers of unemployment rates which sit at half-century lows, it could take even longer to slow inflation.

And time isn’t on the side of people choosing between food and shelter.

What if this plan isn’t working?

Join me next week, when I’ll put that question directly to Bank of Canada Governor Tiff Macklem.

Correction — Nov. 24, 2022: About 35,000 homes were sold in Canada in October 2022, not 425,000, which represents the annualized number first reported. As well, this article inaccurately reported that Blackstone, a global investment business, is ready to spend $50 billion on Canadian assets.