Colette Murphy is the Executive Director of the Atkinson Foundation.

In the same year as the Unemployment Insurance Act was passed by the House of Commons, Joseph Atkinson turned 75.

The effects of the Great Depression had been so intense that in 1940 federal and provincial governments were finally willing to take bold measures to prevent its repeat and to mitigate the unpredictability of the economy. They were also ready to reform and expand programs initiated a decade or two earlier like old age pensions, veterans’ benefits and labour standards.

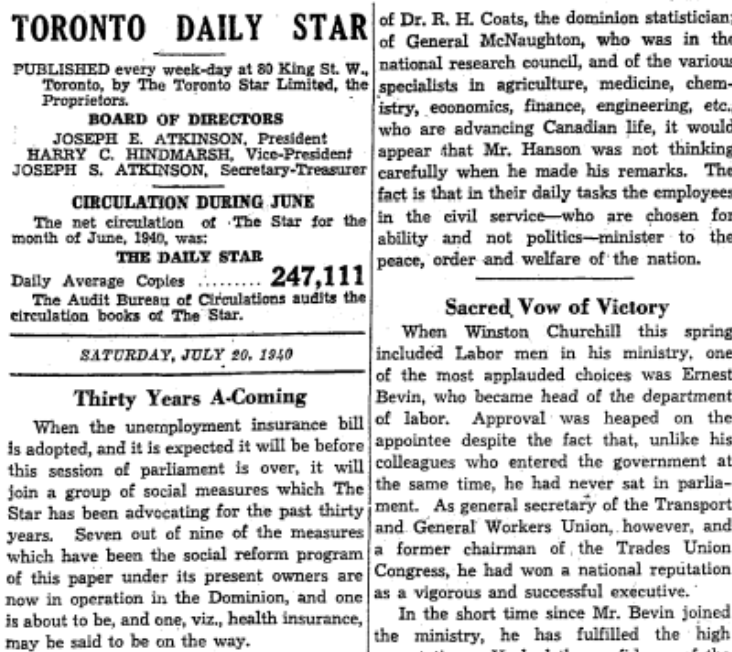

This political victory was “thirty years a-coming,” wrote Mr. Atkinson in a Toronto Star editorial that summer. It represented “much hope and striving on the part of many individuals and groups,” he said. Many who started the fight didn’t live to see this day, but those who did had every reason to believe Canada’s social safety net would only get stronger with time.

When Mr. Atkinson established a foundation two years later, he wanted to be certain that his grandchildren would inherit a better society than he had. His aim was to find a way to keep citizens engaged and keep the pressure on legislators and their advisors when he no longer could. As it turned out, his caution was well placed. After an initial period of expansion, unemployment insurance and other national programs began to decline.

The erosion of Canada’s only decent work program is thoroughly documented by Dr. Donna Wood in a paper published in June 2017 by the Mowat Centre. It’s called The Seventy-Five Year Decline: How Government Expropriated Employment Insurance from Canadian Workers and Employers and Why This Matters. In the paper, she explains the structural and financial changes that began to impair the program’s effectiveness as early as the 1960s when the federal government took over control of the Unemployment Insurance Commission.

Through the 1980s and 1990s, successive governments narrowed access, reduced premiums, and raided employment insurance funds to hit deficit reduction targets, pay for other programs, and make tax cuts. Today, the percentage of unemployed workers eligible for EI hovers around 40% – down from 81% in the early 1980s. In Toronto, the coverage rate is lower than 30%. Not only has EI not kept pace with changing labour market realities, its original intent – anticipating and sharing the risk of unemployment equitably among workers, employers and the federal government – has almost disappeared.

Dr. Wood’s paper inspired us to reach out to colleagues at the Mowat Centre and Broadbent Institute. This summer, we started a conversation about the program’s original intent and who decides what changes are needed to ensure its relevance well into the 21st century. On October 20th, 30 people with a wide range of policy perspectives and from different sectors will join our discussion on this question of relevance. We’ll also share our perspectives on EI as a plank in Canada’s social architecture as well as its prospects for renewal during this roundtable.

The Atkinson Foundation has been preoccupied with the continuous renewal and continued relevance of this architecture for 75 years now. While debate about its size, scope and structure has been a constant in recent years, we have heard little discussion about the values at its base. Further, the circle has been much smaller than it must be for a true national consensus about its future to emerge.

Younger workers and newcomers are largely missing from the conversation. They’ve not found a sense of security in social programs designed for a very different economy. Nor do they know the old stories behind the choices and trade-offs that created the modern welfare state with universal benefits and a bias against means testing. Their experience doesn’t include stable jobs supervised by a single employer or governed by predictable schedules and workplace conditions in return for a regular salary and benefits.

While many pay into programs like EI and the Canada Pension Plan, they don’t expect to benefit from them during work slow downs or after they can no longer work. They simply do not identify with those who do. Many are discouraged while others become more complacent. The result is a country more deeply divided along race, class, gender, and generational lines; a country that could become more lonely, fearful and angry unless we turn toward each other.

The economic and political insecurity that produced strong feelings of social solidarity in the last century is stirring equally strong feelings of abandonment, resentment and cynicism in this new one. It’s driving a wedge between unionized and non-unionized workers, owners of larger and smaller businesses, and governments at all levels. This wedge cannot be permitted to get any bigger.

It’s time for everyone – no exceptions – to expect a much broader and more ambitious national conversation about how we look out for and take care of each other. It must be a dialogue among people who are ready to use their democratic power for the public good, not a survey of stakeholders who have a private interest in the outcome. Their capacity to listen with empathy and respect is even more valued than their ability to articulate a persuasive point of view.

This kind of dialogue is not a one-off, the kind we have in roundtables or consultations. It’s not a workshop for fixing a broken system or tinkering with policy options. It requires the full participation of people who have no special resources or expertise other than a legitimate share of responsibility for decisions that affect them. Getting young people – and anyone who has been historically excluded – into the conversation has to be a priority. Progress depends on our collective commitment to stick with it for as long as it takes to sort out what we can expect from one another – the risks we can best shoulder together and the rewards we want to share.

The stakes are just as high if not higher than they’ve ever been. No one will be able to take comfort much longer from imagining how much worse things were in the Great Depression. A “grim milestone” is in sight, some economist say, and it sets a new low mark. Our best hope, however, is a turn in the direction of a more relevant, inclusive and renewed vision for EI and the rest of Canada’s social safety net without any further delay.