Colette Murphy is the Chief Executive Officer of the Atkinson Foundation.

“We’ve lost a giant,” wrote Pedro Barata the day after we learned Dr. Charles Pascal had died suddenly. “Charles was relentless. He leaves us such a rich legacy of progressive policies and strong organizations pushing for social justice. So many of us benefited from Charles’ wisdom, time and belief.”

Ever since I heard the news last Monday, I’ve been thinking a lot about Charles and the skilful people who anchored Atkinson from 1996 to 2010. They were a formidable team. Together with a committed group of board members, they helped to usher in a new era in philanthropy — one that is less about the private care provided by benevolent and generous givers to the so-called “disadvantaged,” and more about the strategic pursuit of systemic change to create a public ethos of mutual care.

Charles wrote this insightful retrospective in 2009 entitled With My Hand On the Doorknob: In Search of Strategic Philanthropy. Under his leadership, Atkinson’s goal was “to move from reacting to proposals for ‘good works’ to becoming a proactive organization, working with partners to advance evidence and ideas about how the future could be more just.” Key to achieving this goal was channeling energy and moving money from “bricks and mortar” to “the architecture of ideas” — big ideas with the power to drive change in political culture and public policy.

The ideas that captivated Charles are well-known: universal, publicly-funded, and high-quality early childhood education, an index to measure the wellbeing of a country in addition to its GDP, and a tax benefit for people caring for children on low-incomes. He pursued imaginative and pragmatic multi-stakeholder responses to complex, seemingly intractable and often divisive issues. Moreover, he put stable, long-term funding arrangements, with very few strings, behind exciting leaders and organizations who were breaking old mindsets with innovative strategies.

Charles didn’t devote himself to positing theories, writing books, or giving lectures about strategic philanthropy. He certainly could have given his powerful intellect, depth of knowledge, and academic credentials. He chose instead to focus on demonstrating what’s possible. I’ve been told that the Atkinson team huddled in Charles’ office to strategize each morning. They talked about how they would mobilize resources, communicate with partners and other stakeholders, earn media attention, and help build coalitions big and strong enough to withstand the forces of opposition and pessimism. The team’s fidelity to the Atkinson Principles was their superpower.

As the first professional employed to run the Foundation, Charles built a durable organization on the base of these principles and approach to strategic philanthropy over fifteen years. That’s how the first Atkinson generation continues to inspire and inform the next one. It’s always hard for new hands to turn the doorknob and enter a space shaped by an earlier time. Charles made it easier by leaving behind a sturdy platform and substantial body of work that reminds us to whom the Foundation is accountable: the people who have no special wealth or influence, and whose voices are too often ignored in places where decisions about them are made.

Betsy Murray, a former Board Chair and the granddaughter of Joseph Atkinson and Elmina Elliott, described Charles’ time as executive director this way at our 75th anniversary celebration in 2017:

“It was an era of remarkable creativity and productivity. Brilliant and relentless advocates made great strides with the Foundation’s support. They pursued an agenda that included early childhood education, Medicare, public education, Indigenous rights, corporate social responsibility, and several issues related to economic justice. Bold ideas like the Canadian Index of Wellbeing, the Atkinson Centre for Society and Child Development at OISE/University of Toronto, the Atkinson Economic Justice Fellowship, and the Atkinson Fellowship in Public Policy were advanced. And together we helped make Canada stronger and more resilient even as the country started showing the signs of stress caused by growing inequality.”

These stresses have only become more obvious and complicated in the last ten-plus years. Giants like Charles are made through the transformative process of taking on giant-sized problems and solutions. It’s hard to believe that we’ve lost him when the stakes are so high. I can only imagine he would want us to stay focused on the work and on nurturing the potential for giant-sized leadership in everyone, especially young people.

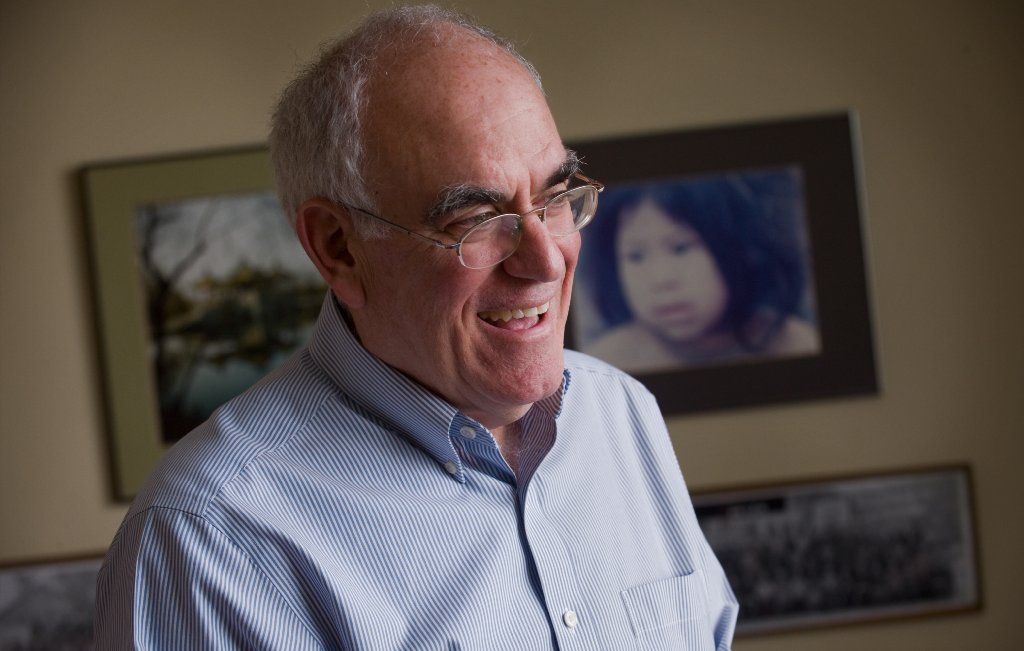

A children’s book called How Do You Feed a Hungry Giant? by Caitlin Friedman came to mind when I saw this picture of Charles last week. It was taken during the period he was the Special Advisor on Early Learning to then Premier Dalton McGuinty and the Government of Ontario.

The author offers a “gentle lesson” about being there for each other, even if your fellow human is a giant. In Kid Lit, giants are usually irascible but this book says they just might be thirsty and “hangry” too — like Charles.

In the 2000s, I worked with him on the City of Toronto’s Children and Youth Action Committee, the Funders Network Against Racism and Poverty, and on a provincial poverty reduction strategy. We shared a commitment to the Workers’ Action Centre, Voices from the Street, and others who organize people in low-income neighbourhoods to participate in democratic decision-making processes.

I will always remember Charles as he was then: a courageous man with an unquenchable thirst for justice, an insatiable hunger for promising solutions, and an uncompromising belief that we can all be fed.